Judges and a long battle for law enforcement in Kenya | Kenya

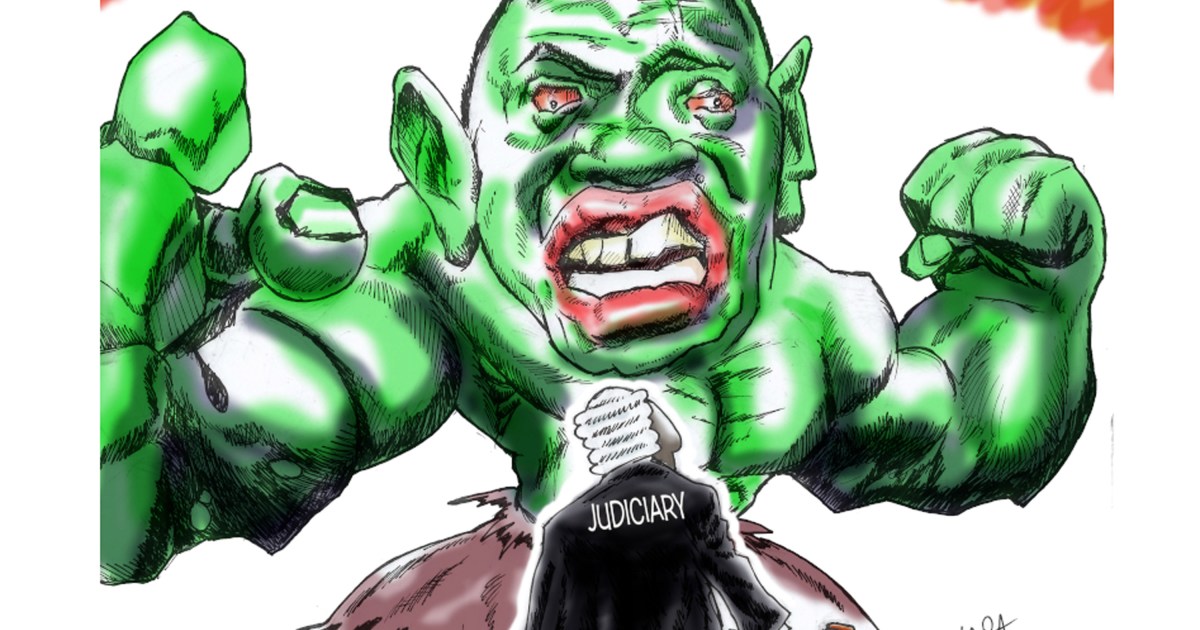

Conflict between Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and the country’s judiciary over the supremacy of the law has once again become apparent. This time the war escalated when the president tried to usurp the power of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) to appoint judges and judges in the country’s courts.

For two years, in a court of law, Kenyatta refused to formally nominate 41 JSC nominees for various positions, including the Supreme Court. This is contrary to the laws of this country, which would not give him the opportunity to use the case, and many court decisions that prove this. This week, he listened a little, and chose 34 of them, but further continues to ban six others (one died shortly afterwards).

His view has been widely criticized by government agencies, members of parliament and even former attorney general Willy Mutunga, who wrote a scathing letter accusing Kenyatta of being “disturbed by the use of force” and taking his oath. But this is not the first time Kenyatta has been confused by the courts which, especially since the enactment of the law 11 years ago, have been bold in seeking to enforce the rule of law.

For a long time in Kenya’s history, independence has become a myth. During the colonial period, judges served as Crowns and lacked freedom. As Mutunga observed in 2013, they were “government employees, harassing colonial officials and did not want to be involved in this”.

Although there was a measure of independence in 1963, the law protected judges, deliberately removing them from senior positions, it did not appear to be in conflict with the harsh judicial practices established by colonial rule.

Over the next 47 years, with the exception of a few visible ones, the courts not only remained silent, but seemingly desperate as a successor to their allies to overthrow all defenses and restrictions. Judges just sat as a department in the attorney general’s office, underpaid and underpaid.

In a landmark case in 1989, a judge ruled that all rights reserved were invalid and unenforceable, in particular, depriving all Kenyans of their security, as the Supreme Court had failed to establish court rules by the Supreme Court.

Perhaps the lowest level of legal impetus came in the 2007 election crisis, when a lack of confidence in the autonomy of the opposition led to protesters taking their cases to the streets, killing more than 1300 people, displacing hundreds of thousands and destroying the country. In the aftermath of the violence, independent courts were at the forefront of reformers, who have been fighting for legal and court reform for more than 25 years.

In many ways, the 2010 law was re-enacted that promulgated freedom and removed many of the political reforms it offered to Kenyans. The independence law failed mainly because it was ruled by the British, the politicians who received it did not trust it and, after almost a century of colonial oppression, there were few institutions that could defend this.

In contrast, the 2010 Constitution was drafted as a result of the long-running civil war, international questioning and the presence of a group of Kenyan human rights activists, lawyers, and civilians who wanted to stand up for themselves. Most importantly, after being freed from the shackles of the chains, the courts are changing their backs quickly and affirming their responsibility to enforce national law.

It wasn’t a straightforward change of pace, however. Some interpretations of the courts seem to be a distraction from the previous days of Kenyan rule. The 2013 elections, which said the Justice Act did not require the defendants in the International Criminal Court to remove their names before running for office, prompted President Kenyatta and his deputy, William Ruto, in a highly contested ruling, sparked widespread protests. many in Kenya fear that the future may be too old.

The courts also rejected antitrust laws, which did not imply that homosexuality is a marriage and that by recognizing the right to same-sex marriage, the law prohibits homosexuality.

However, for the most part, the courts seem to have found some of these and have gained confidence from Kenyans by, more than once, violating laws that violate the law and, in preparation for the 2017 elections, enforce laws that would make fraud more difficult for citizens to recognize.

Undoubtedly, the main issue came with the cancellation of the presidential election that year, which was not expected before. This threatened Kenyatta to “resume” and two months later, following the deputy prime minister’s attack, the Supreme Court failed to include a number of hearings against the repetition before the problems that led to the ban were resolved.

Although he “won” a second time, Kenyatta continued to fight for justice and the rule of law, teaming up with his former ally, Raila Odinga, to establish a Building Bridges Initiative – a secret effort to restore order and change the Constitution to reinstate a powerful man. This led to the creation of a document that provides for a change in a number of laws.

As in the 1960s, today counselors were not considered a check for an adult and it fell to the judges to ban the bill. In May, in a landmark decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the business was illegal.

In a ruling that expressed concern over the way in which independence had been curtailed through the reform process and how Kenyans were pushing for change, the judges said a breakdown in the constitutional process could be perpetrated by a participatory parliament in Kenya.

Once again, the verdict has sparked outrage and frustration with Kenyatta and his detractors and he has retaliated. Two of the judges whose appeals were upheld by the Supreme Court of Appeal were part of a five-judge panel that handed down the verdict.

In a scathing statement in early June, the President declared that the purpose of human rights and independence was an agreement with the government and that the exercise of the right to justice was a violation of the same laws that give freedom.

As the courts now prepare to hear the government’s appeal against the ruling by the end of June, the question remains as to whether the judges will be given the courage to comply with the agency’s demands or whether they will have the courage to continue defending the law and independence. Kenyans will take a closer look, hoping they will.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editor of Al Jazeera.