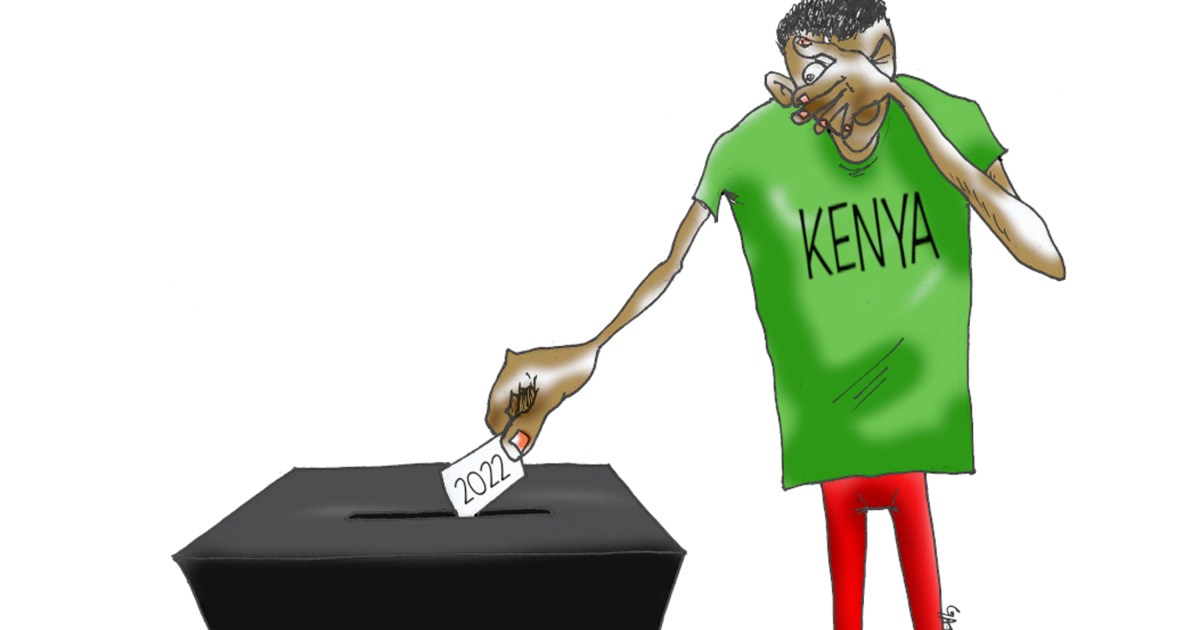

For Kenyans, 2022 brings hope and fear | Choices

As in the rest of the world, 2021 has not been the best years for democracy in Africa. It has seen the return of militants from West and Central Africa, Sudan, Guinea, Chad and Mali. In Sudan, the putsch reversed the democratic transition that paved the way for the end of military rule for many years.

And as it became apparent that democratic progress was finally reaching the Horn of Africa, civil strife and political violence returned, as was the case in Ethiopia and Somalia. In Uganda and Tanzania, free and fair elections have proved to be an elusive goal.

During this difficult time, Kenyans are preparing to meet their own demons in eight months. The country has a very difficult relationship with elections, especially presidents. They have sometimes been instrumental in defining the interests of the masses, as was the case in 2002 when the successor to President Daniel arap Moi, Uhuru Kenyatta, was defeated.

However, five years later, the country was on the verge of a split following the disputed election results. Since then, elections have been events that promote greater hope for change and dread of the consequences.

The last two presidential elections have seen this work. In 2013, the terrorists won because the memory of the 2007-2008 violence led to the abolition of the election, which was the first time under a new law enacted in 2010, which was at the end of 25 years of anti-electoral law. was fueled by a spate of violence two years ago.

Although there is ample evidence that the election was not held in accordance with the law, the newly formed court, led by Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, a well-known democrat and lawyer, tried to declare the results false. As a result, Uhuru Kenyatta became President.

In 2017, Kenyatta’s bid for re-election failed when the Supreme Court, this time under the leadership of David Maraga, a highly regarded tribunal whom many human rights activists consider to be Kenyatta’s company, overturned the election for disobedience. law. This was the first time that a tribunal in the continent had again suspended a presidential election, signaling another victory for hope.

However, in the by-elections held in October of the same year, fears prevailed again. A day before the election, the Supreme Court was due to hear a verdict of appeal after Kenyatta’s main rival, Raila Odinga, was released two weeks earlier. However, most of the judges in the court decided not to go to court, because of the intimidation after the dismissal and the plot that killed the second guard for the trial judge. This paved the way for “elections” that were not uncommon and that left the country very divided, and many of Odinga’s supporters died.

Today, as the world looks down on another election, there are reasons to be optimistic and pessimistic. Last year the courts showed courage in defending the country’s constitution, and put relief on what Kenyatta (and his new ally Odinga) tried to change.

In addition, elections, where leaders lead, make it increasingly difficult for violence to occur. Since 1992, the most violent non-violent presidential elections have taken place in 2002 and 2013, when the border barred Moi and Kibaki from running for office. Kenyatta faces the same barrier next year and, as in the past, politicians, government officials and security forces may have restrained themselves, not wanting to retaliate against the winners, whether it was Odinga or Kenyatta’s deputy, William Ruto, if they found themselves. on the lost side.

On the other hand, Kenyatta has a horse in the race, thrown behind Odinga, and his desire to intimidate and incorporate independent organizations has not diminished. Maraga has retired and her successor, Martha Koome, a well-known lawyer and human rights lawyer such as Mutunga and the country’s chief justice, is not showing any interest in fighting government officials.

In addition, the electoral system has not changed since 2017 disrupted and tends to be persecuted. In fact, many observers are still alive and well. There is no reason to believe that it would not be helpful for people who want to steal elections.

Despite the challenges that 2021 faced, support for democracy across the region remains high, depending on the elections. The people of Kenya have no doubt hoped that by 2022 hope will prevail again.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Al Jazeera.