How Unilever’s tea business became a test of private equity’s conscience

As Hellen Nyaboke and her family tried desperately to flee attackers on the Kenyan tea estate where she lived and worked, her husband Kenneth Mayenga was killed with a machete. One of her sons was beaten to death. Stricken by terror that she would be next, she hid among the tea bushes.

Nyaboke has spent half her life working for one of the world’s largest consumer goods groups, Unilever. But after the violence, fuelled by ethnic tensions, broke out amid a disputed election in 2007, she says the company did little to help.

Nyaboke says she received Ks12,000 (£78) in compensation after the attacks, and with the help of the company, she and other survivors fled to Kisii County more than 40 miles away. But she believes she should have received more after losing two family members and enduring six months without pay after the violence.

“The only thing we were left with was the clothes we were wearing,” says Nyaboke, now 48. “All these years I tried to get fair compensation from Unilever but it was not possible . . . they ignored me.”

Almost 15 years after the attack on the plantation in Kericho, in which at least seven people were killed and 56 women raped, according to a complaint filed with UN human rights bodies, many workers are still seeking compensation and funds for medical treatment from Unilever.

The company says it provided “significant support” to the victims of the 2007 violence, including medical aid, counselling, replacements for looted possessions and retraining options. But the complaint to the UN — filed by 218 Kenyans last year, alleges that Unilever knowingly placed its workers at heightened risk of attack, failed to help them afterwards and stopped their wages for six months.

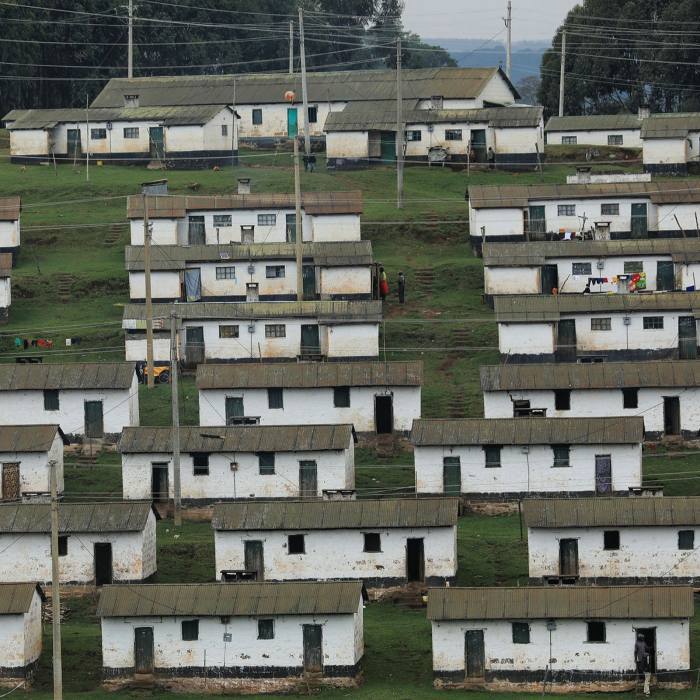

The relationship between the company and the plantation workers is complex and unusual in the corporate world. Unilever provides housing for up to 30,000 people, education and healthcare services for workers and their families at the plantation in Kericho. But, those ties are about to be broken after Unilever agreed to sell its tea business — owner of PG Tips, Lipton and Brooke Bond, along with plantations in Kenya, Rwanda and Tanzania — for €4.5bn to the private equity group CVC Capital Partners.

The legacy of the violence, along with what workers describe as harsh day-to-day conditions in an industry known for hard labour and low pay, presents a challenge for the buyout group that will take the plantation on. The private equity industry has increasingly touted its sustainability credentials, as the pension funds that fuel its dealmaking have started asking more questions about ethical standards.

“CVC has an ingrained commitment to environmental, social and governance issues and has made them central to our investment process and the stewardship of our businesses,” the company says. It adds that the consultancy firm EY visited the plantation in Kericho for CVC — part of its due diligence before its bid — and found Unilever had “industry-leading” policies and procedures. EY declined to comment, citing client confidentiality.

Unilever says it “fully rejects any allegation that it failed in a duty of care to employees or their families in the tragic events following the disputed 2007 elections in Kenya. An international commission of inquiry clearly concluded that the scale and speed of the violence that erupted was unforeseeable and Unilever Tea Kenya took all possible steps at the time to protect staff and dependants, subsequently providing significant support to all affected.”

Two of the three final bidders for the tea business, buyout groups Advent International and Carlyle, pulled out, at least partly, over concerns surrounding the plantations. An indication, say people close to both buyout groups, that even in private equity, with its relentless focus on profit maximisation, fears over the social or reputational consequences of deals are gaining traction, as ethics and sustainability rise up investors’ agendas.

The deal has become a testing ground for how private equity groups approach workers’ pay, conditions and safety in a climate where investors are scrutinising their ethics.

“The whole ESG [environmental, social and governance] lens across these sorts of investments is so much more of a factor than it was before,” says one person involved in the deal.

From the plant to the teapot

Unilever’s Kericho plantation, established by a Briton called Malcolm Fyers Bell for the Brooke Bond tea company in 1924, was the first commercial tea estate in Kenya.

Keen to expand tea cultivation outside China, the British set up plantations in Asia and Africa in the 19th and 20th centuries. They often brought a workforce from elsewhere to the remote areas suited to tea growing, says Sabita Banerji, chief executive of Thirst, an umbrella group campaigning for human rights and sustainability in the tea industry.

Plantation founders created “a structure of having a workforce that lives on the tea plantation, in housing provided by the management, and therefore completely dependent on [the management] for their livelihoods. That has persisted, not only in India, where it started, but it spread through the British empire to Kenya, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh,” Banerji says.

Unilever has built 23 primary schools, 50 nurseries, housing for 30,000 people, 23 pharmacies and a hospital in Kericho. It also offers paid annual leave, paternity and maternity pay, and transport allowances, plus free food during working hours, the company adds. The Financial Times did not visit its plantation in Kericho, where Covid-19 restrictions are in place, but spoke to former workers and union members in the neighbouring town.

Sir Thomas Lipton, founder of Lipton tea, Unilever’s largest tea brand, established a plantation in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, in 1890. He boasted, as Unilever’s tea division — now known as Ekaterra — does today, of owning the supply chain from plant to teapot. Lipton and his contemporaries brought tea to the mass market. But the model they pioneered has left the industry operating on narrow margins and tea workers — a largely female workforce — vulnerable to exploitation.

Between 2008 and 2013, a Dutch NGO and a TV documentary separately alleged sexual harassment of women workers by some of the senior staff on Unilever’s Kericho estate. Unilever responded by introducing new training, more female leaders, new dedicated welfare and human resources roles, peer counsellors and an ethics hotline.

The complaint against Unilever over the 2007 violence was lodged with the UN working group on human rights and transnational corporations and the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. It alleges some victims received about £80, equivalent to one month’s wages, in assistance, but this “represented a small fraction of the loss of wages and possessions they had suffered”.

The claimants attempted to have the case heard in the UK but the courts ruled it should be pursued in Kenya, a route the claimants argue is impossible because of the risk of reprisals. Nyaboke says her family was targeted in the post-election violence because they, along with many other plantation workers, belong to the Kisii ethnic group, which was perceived as supporting the then president Mwai Kibaki.

If the complaint is upheld the UN bodies could find Unilever to be in violation of UN principles and recommend it address any shortcomings, but they cannot enforce penalties.

Even so, such a rebuke from the UN would leave a black mark on Unilever’s record. Successive chief executives, going back decades, have emphasised the company’s dedication to sustainability and social purpose, helping the group to score highly on ESG metrics. Chief executive Alan Jope has pledged to pay all workers in the company’s supply chain a living wage by 2030; Unilever says Ekaterra will retain that pledge after the sale.

Yet two former executives say the company has struggled to apply its principles at the plantations. One says Unilever paid better wages than rivals but battled to reconcile fixed costs with volatile tea prices. “The consumer price of tea has to be determined by what the market can pay,” he adds.

Francis Atwoli, secretary-general of Kenya’s Central Organization of Trade Unions, says Unilever had formerly been “the best employer” but in recent years its Kenyan arm had been “overwhelmed by maximisation of profits”.

Daniel Leader, a lawyer at Leigh Day who represents some victims of the 2007 violence, says that if Unilever is found to have breached UN principles in Kenya, “that would inevitably beg the question as to whether Unilever practices what it preaches”.

Profit maximisation

The company is currently reviewing its compensation payouts after the 2007 violence. “Unilever Tea Kenya . . . felt that the right thing to do was to review if any claimants had not received the support it offered to other employees at the time and, if so, to make up for what they missed,” it says.

Thulsi Narayanasamy, head of labour rights at the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre — a non-profit organisation not involved in the UN complaint — argues that as the world’s largest tea maker Unilever could have pushed for a better deal for workers.

Unilever “has really significant leverage when it comes to the pricing of the tea across its global supply chain. This is where the cost that it decides to pay really sets the standard for the industry,” she says.

Over the past decade there have been profound changes on the plantation in Kericho after Unilever introduced tea harvesting machines, leading to job cuts. Dickson Sang, secretary of the Kenya Plantation and Agricultural Workers’ Union in Kericho County, says that the number of staff on the Kericho site eligible to join a union dwindled from 25,000 to 12,000, of whom only 4,000 are permanent employees. Unilever says 5,500 permanent workers are now employed there, with more in peak season.

Hand pluckers say their daily pay fell as they had to walk long distances to find tea that the machines had not picked. Pay is determined by the quantity of tea harvested, but Unilever says it is always topped up to a daily minimum.

The company denies that mechanisation has affected pay rates, saying “changes in take-home wages for field plucking staff may vary because of the seasonal nature of tea crops, or because some workers pick more in a day than others — not because of mechanisation”.

Geoffrey Nyambane had earned Ks30,000 (£195) a month before mechanisation but afterwards his pay dropped closer to the union minimum, coming in at less than Ks12,400 in February 2018, the year he left, according to payslips. For Nyaboke starting in January 2016 her monthly pay fell to less than half of her normal basic wage, she says. Unilever says its union-agreed minimum pay rates are about two and a half times Kenya’s minimum agricultural wage.

Unable to find work elsewhere, Nyaboke remained a Unilever employee until she took a voluntary retirement deal in December 2018. There were no compulsory redundancies, but Sang says many workers struggled with lower pay and reluctantly agreed these retirement deals, which in 2018 included 23 days’ pay for each year of service, notice and leave pay, and a one-way bus fare. Those with more than 10 years’ service received 55 days’ pay per year worked.

Unilever says the early retirement offer was oversubscribed, adding: “All workers granted voluntary retirement were given the terms clearly set out.”

With elections due in August, there are concerns for those still with the company. Sang says new security measures are needed. “If things are not done now, with the [next] election we could have a similar scenario of violence,” he adds.

Doing the deal

By then, Unilever’s tea arm may be owned by Luxembourg-based CVC, which agreed to buy the business in a deal expected to be completed in the second half of this year. Under the deal, CVC will be sheltered from any potential future cost of claims over the treatment of workers during Unilever’s ownership, a move that is common when corporations carve out and sell business units, a person with knowledge of the matter says.

Advent and Carlyle both dropped out at a late stage in the bidding auction. Advent excluded the plantations from its offer for the group, which was more than €750mn below CVC’s winning bid, according to two people with knowledge of the matter. Carlyle dropped out just days before the bid deadline.

Advent’s executives were worried about the cost and difficulty of supporting a workforce that is dependent on the plantation for their livelihood, and the potential for bad headlines should things go wrong, says a person close to the private equity firm. Concerns about the potential for violence during elections in August was another deterrent, he adds.

“The plantations are a whole different ball game” compared with situations private equity firms are used to, says a second person close to the Advent bid. “You take on responsibility for these workers’ health, their education, their protection.”

Carlyle had similar concerns, a person close to its bid says. “This is not like buying a factory where everyone goes home at the end of the day,” he adds.

CVC did not buy the company predominantly for its plantations. Instead dealmakers saw a chance to apply a well established profit maximisation strategy: separate an unloved unit of a large conglomerate in the hope it will attract a higher valuation on its own.

That means expanding the market share of brands that CVC believes Unilever has neglected, potentially paving the way for a listing or sale at a higher multiple of earnings in a few years’ time. “While there are always areas in any business that can be improved on,” CVC says, “there is a real opportunity here to act as a responsible ESG-focused investor.”

Labour rights advocates are sceptical. The problems on the plantation demonstrate how institutional investors are overly focused on assessing “the human rights policies of companies, rather than the implementation of those policies”, says Narayanasamy.

She fears the sale will not help. “The potential for this sale to have really significant ramifications, driving down working conditions and human rights, is very considerable,” she says. “It’s much harder to hold a private equity company to account.”

Additional reporting by Donald Magomere in Nairobi

Source link