The summer of inflation: will central banks and investors hold their nerve?

After three decades as a bond investor, Jim Leaviss has witnessed plenty of false alarms over the return of one of the biggest debt market nemeses: inflation. But as his screen flashed with Wednesday’s US consumer price index figures — showing a 4.2 per cent annual rise — he felt the stirrings of a new era in financial markets.

“It’s always been right to be sceptical when someone says ‘this is the year that inflation comes back’. But for the first time you can say this time is different,” says Leaviss. “The pandemic might be the systemic earthquake that changes the inflation outlook we have been used to for the past 30 years.”

A summer burst of inflation was always inevitable once lockdown measures began to ease: a year ago the spread of Covid-19 had crushed economies around the world, sending commodity prices plummeting and even pushing the cost of a barrel of oil in the US below zero.

Central bankers — particularly at the US Federal Reserve — have been at pains to insist the current bout of price rises is temporary, and will not push them to an early unwind of the massive monetary stimulus actions they launched last year to combat the fallout from the pandemic.

Those assurances, however, have not deterred a growing number of investors from becoming unnerved that a groundswell of deeper inflationary forces may soon test these policymakers.

A prolonged bout of inflation could hamper the post-pandemic recovery, potentially forcing the Fed and other central banks to quickly tighten its monetary screws. Also at stake is one of the most remarkable rebounds in financial history, which has seen equities and other risk assets leap from one all-time high to the next thanks to historically low borrowing costs.

Investors this week got an inkling of the potential pain to come, with the technology-heavy Nasdaq Composite among the indices falling in response to this week’s inflation data, before recouping some of those losses.

“It’s just one data point, but it’s the first blowout that shows inflation is really hitting consumers,” says Leaviss, who is head of public fixed income at M&G Investments. “Yes, it’s a reflection of where we were a year ago, and we know there are supply disruptions. But there comes a time when you can’t explain all of this away as one-offs.”

Before Wednesday’s CPI report — which Rick Rieder, BlackRock’s chief investment officer of global fixed income, called “jaw-dropping” — inflationary signals were already beginning to flash.

The cost of commodities critical to the global economy, including copper and iron ore, has soared. A semiconductor chip shortage has hampered new automobile production worldwide, driving buyers to seek out alternatives in the pre-owned market. Prices for used vehicles rose 10 per cent on a month-by-month basis in April, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Home prices have rocketed higher as well, alongside swelling lumber prices. A startling shortage of workers has emerged in several countries, too.

“It is not just oil. It is not just copper. It is lumber. It is the fact that people cannot find workers. All of this together makes me think that inflation may have more legs,” says Sonal Desai, chief investment officer at Franklin Templeton’s fixed income group.

“There is an entire generation of traders who have grown up investing in the post-global financial crisis world of no inflation,” she adds. “People shouldn’t underestimate how uncertain things will look if we are entering a new paradigm.”

Dropping the pre-emptive approach

Since Paul Volcker raised US interest rates to a record 20 per cent in the early 1980s, controlling inflation has been woven deep into the DNA of the world’s central bankers.

With their inflation-targeting frameworks, these policymakers tended to act swiftly by raising interest rates at the merest whiff of a return to the inflationary 1970s. That held true in the years following the global financial crisis of 2008-09: Jean-Claude Trichet at the European Central Bank in 2011 and the Fed’s Janet Yellen in 2015 both started raising rates to stave off ascendant consumer prices.

Jay Powell, the current Fed chair, has taken the Fed in a different direction — culminating in August’s shift in the policy framework to explicitly tolerate periods of higher inflation in recognition that premature tightening by the central bank in the past along with fiscal austerity had prolonged the previous recovery.

Most other central banks have yet to mimic this so-called “average inflation targeting” but have nevertheless broken new ground with their pandemic responses. The current bond-buying programmes of the ECB and the Bank of England dwarf earlier ones in their scale.

“Central banks seem to have dropped their pre-emptive approach for dealing with inflation,” says Mark Dowding, chief investment officer at BlueBay Asset Management. “Instead, policymakers seem to be cheering it on from the sidelines.”

Few would argue this monetary largesse on its own should fire up prices, especially with deflationary impulses such as ageing demographics and technological innovation in play. Rather, it is how governments have responded to this crisis that has been transformative. Borrowing levels have exploded throughout the developed world, and the spending taps are still open.

The US has gone furthest with Joe Biden’s $1.9tn stimulus programme enacted in March and the promise of $4tn more in infrastructure and social safety net investments over a decade, if he can get sufficient congressional support. Even the more fiscally cautious eurozone has joined in with the bloc’s €750bn recovery fund.

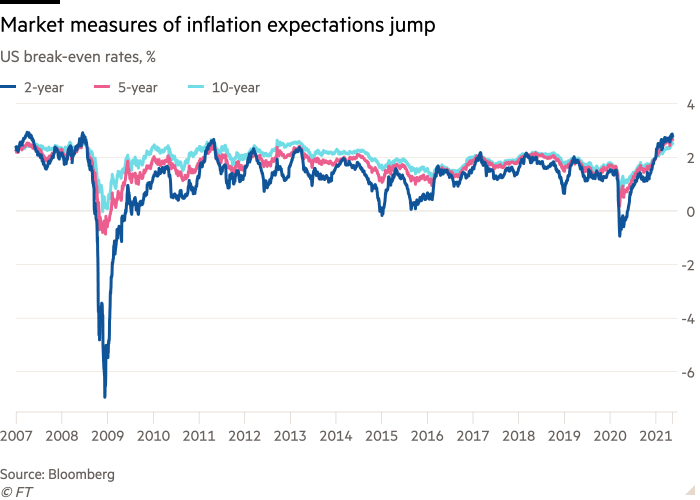

Little wonder then that market-based inflation expectations really began to climb following Democrats’ legislative victories in January, which handed power over government spending to Biden’s party. The two-year break-even rate, which is a popular proxy for future inflation and is derived from prices of US inflation-protected government securities, now sits above 2.8 per cent, while the 10-year measure has risen to 2.5 per cent.

“People underestimate the role that austerity played in the deflationary pressures of the last decade,” says Karen Ward, chief market strategist for Europe at JPMorgan Asset Management.

Testing the Fed

Fed officials have so far brushed aside any concerns that bottlenecks in supply chains tied to the reopening of economies and enormous fiscal support will compound into something that compels the central bank to waver on its pledge to keep policy ultra-accommodative until its newfound goal of a more inclusive recovery is achieved.

Powell was adamant at the April meeting that the Fed has not yet seen “substantial further progress” towards its inflation and employment targets to warrant an adjustment to its $120bn monthly asset purchase programme.

Fed governor Lael Brainard on Tuesday echoed these remarks, urging patience in the face of a “transitory surge” in inflation — a message also delivered by vice-chair Richard Clarida this week. Even policymakers at the ECB, including German economist Isabel Schnabel, have dismissed near-term upticks.

Market pricing for future interest rates reflect the Fed’s success so far in quelling concerns about its ability to control consumer prices. One popular barometer, eurodollar futures, indicates that the central bank will begin raising rates by early 2023. While that is roughly a year earlier than the Fed’s most recent projections, it does not suggest widespread fears about runaway inflation.

“We are in a new era with the Fed,” says Anne Mathias, a senior strategist at Vanguard. “They have a new reaction function . . . [and] this is their first trip around the track with it.”

Investors lament, however, that they have been left guessing not only how the Fed defines “transitory”, but also the specific parameters that motivate a change in policy. That leaves the Fed susceptible to a communications blunder as inflationary pressures build this year, according to Vincent Reinhart, a former Fed economist who now serves as chief economist at Mellon.

“The committee is diverse and inflection points are tough,” he says. “Jay Powell is essentially saying, ‘we are going to be driving at top speed into the turn, but trust me, we know when to start turning the wheel’.”

“There will be some committee members who will have white knuckles at that point and will worry,” Reinhart warned. “That then feeds into the inflation jitters.”

Investor angst

Wednesday’s US consumer price figures landed in a market that was already anxious about inflation. A bond sell-off that had been on pause for two months briefly resumed this week, pushing yields in the eurozone to their highest level in two years. US Treasuries also weakened, although yields remain below their March highs and are still close to historic lows. After initially spiking to 1.7 per cent, the 10-year note, a benchmark for financial assets across the globe, fell back towards 1.6 per cent by the end of the week.

Some investors already sense an overreaction. “The market response is odd,” says Gurpreet Gill, a fixed-income strategist at Goldman Sachs Asset Management. “Everyone’s been talking about inflation for months. It’s been telegraphed.”

But the sellers are far more worried about a long-lasting pick-up in price growth than the current spike. Inflation is poison for bonds, eroding the fixed interest payments they offer.

“There’s quite a lot of complacency in this idea that inflation is transitory, and I think that’s born from the fact that a lot of people in financial markets haven’t ever seen any inflation at all,” says BlueBay’s Dowding.

The Fed’s determination to stay the course could also see long-term inflation expectations rise even further — leading to sharper rate rises down the line.

“If you are going to be intentionally late, it means you could have to be more aggressive on the back end of this,” says BlackRock’s Rieder.

That prospect is especially worrying for stock markets, which have surged to new heights led by gains from high-growth companies such as US tech giants. Those companies are valued based on their earning potential far into the future. Investors value those earnings relative to the “risk-free” rate they can earn by buying bonds, so higher yields in effect make them worth less today.

“The last few years have been great for investors because everything went up — you gained on your equities and your bonds,” says Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at Allianz and former co-investment chief at bond group Pimco. “Now you risk losing money on both sides. It’s a horrible environment, and I’m glad I’m not managing money.”

Source link