How China is battling an economic boom

When Jenny Fan received the phone call in early February she thought she had won. The caller, who claimed to be representing a skin care company, told Jenny – a high school student in northern China’s Hebei – that she should receive Rmb1,000 (£ 117) in payment. The reason? Three months ago she bought Rmb200 face cream that did not work on her skin.

The man “claims to be a customer representative of the cream makers”, said Jenny. He offered all the purchases, including a historical photograph, so I had a hard time trusting him.

To get the money back, she told Jenny that she needed to set up a “special payment method” by sending a lot of “experimental” money to a savings account. Once the arrangement is in place, Jenny will receive a refund and a tear compensation.

FT Flic

This article is part of a series of articles written by the new charity FT Flic that develops educational programs to strengthen economic skills for those most in need.

Economics provides young people with a secure future – and can help economically disadvantaged people cope. Join the FT Flic campaign to promote economic education in the UK and around the world

A 19-year-old student paid three Rmb20,000 (£ 2,332). The man soon stopped blocking on social media and stopped singing his calls. Jenny went to the police, but she was told that she was “crazy” for buying the fraud. “They told me the money was gone, because fraudsters on the internet were hard to follow,” he said. “All I have to do is call people I know.”

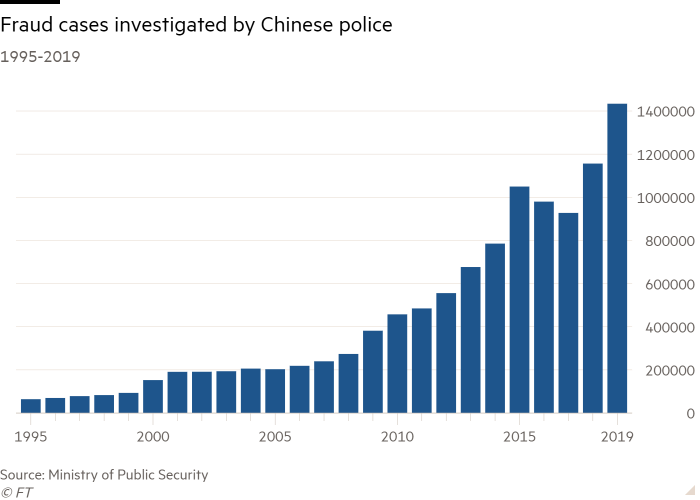

Jenny is one of thousands of Chinese who have been exposed to some form of economic fraud. The crime rate has skyrocketed in the world’s second-largest economy, which boasts of an increasing number of middle-income and middle-income people. “We are seeing an increase in theft while the family economy is declining,” said Nie Chengtao, a Beijing-based attorney who specializes in financial fraud.

Economic reforms have flourished in China, where for decades the rapid economic downturn has brought much wealth and a sense of urgency to the people. Fraudsters have also benefited from the lack of legislation and the government-established roof over deposit rates, which has made it easier for them to convince customers who want to get the most out of their hard-earned money.

The rise of the internet, especially online payments, has exacerbated the problem by making financial fraud easier and more difficult to track. Chinese technology companies are very much focused on developing economic activity. Last year, for example, Fidelity launched a retirement benefit package using Ant, one of the world’s largest financial institutions.

Fraudsters look for customers on the platform, because they can find more people who may be victims than they can reach through public meetings.

All of this has been linked to financial fraud – from the sale of “click farm” membership (where fraudsters hire people to buy goods in online stores for a refund plus fines) to non-financial products – a problem that affects the rest of the world. the whole of China. David Zhang, an anti-fraud lawyer in Hangzhou, said he had committed fraud from college professors to factory workers to high school students. “No one avoids deception. We all have weaknesses that he can take advantage of. “

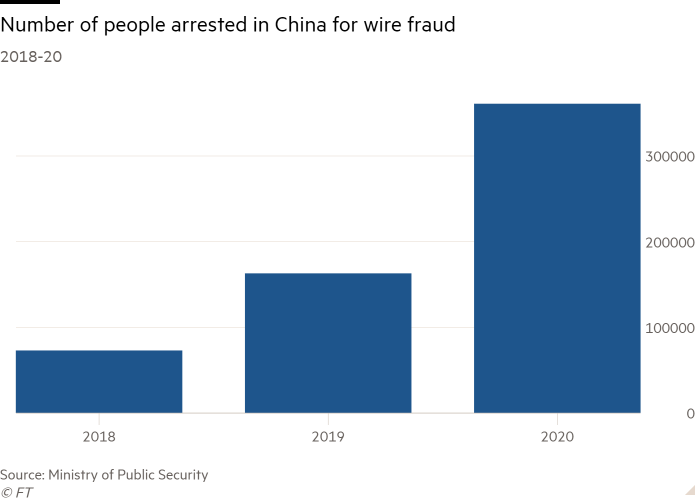

The problem is not a simple one. Despite Beijing’s strenuous efforts to imprison them, and the number of people arrested annually has increased fivefold in the last three years, many fraudsters have emerged unscathed by working abroad or hiding with modern technology.

“We need resources to find fraudulent people,” a Shandong police officer who works for economics told FT.

An international anti-fraud campaign was launched by Chinese authorities in 2019, after President Xi Jinping announced at a conference that tackling corruption is “of paramount importance” in terms of keeping people safe. The campaign culminated earlier this year with the launch of the National Anti-Fraud Center, a mobile app that was downloaded over 500m, making it one of the most popular in the world. Governments use a variety of methods, from street signs to television commercials, to inform people of the nature of fraud and how to prevent it. But the app has also sparked controversy over tracking cell phone use, suspending foreign phones and labeling business programs like Bloomberg News as “jealous”.

Few Chinese officials spend a day free from the false anti-fraud reports provided by the government. Many dormitories have placards in the lobby that tell people not to send money to strangers. Buses carry advertisements on how to detect fraud, while LED screens feature celebrities who want a “human war” against fraud.

Some areas have improved. Last month, Dongjing, a city in Shanghai, began asking guests at the hotel to read and sign fraudulent documents before entering.

“We want anti-fraud education to reach every aspect of human life,” said an official in Dongjing.

One of the potential beneficiaries of this program is a college student who has been plagued by corruption. A survey last year of 2,746 university students across the country by Chinese Youth Daily officials revealed that more than a dozen respondents lost money after being robbed. This led to a new study aimed at educating young people. Last year, Shanghai began recruiting 140,000 college students for online anti-fraud courses, highlighting five well-known frauds, ranging from fraud and online dating.

Some cities are so interested in anti-corruption that Jinan, an eastern city, last year asked university students to allow anti-fraud police to join their social networks. The idea was for the police to send anti-fraud instructions and view suspicious messages. “We want to make sure that students are always protected from criminals,” said Jinan.

Advertisers are another major target for education, as their financial skills fail to keep pace with the wealth of families. A survey of 140,000 executives of the People’s Bank of China in April found that more than half of those surveyed were unable to calculate their annual returns and did not understand what economic diversity meant. Forty-four percent said that they would not simply ignore or read financial agreements.

To reduce the knowledge gap, financial regulators (consisting of the People’s Bank of China, China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the China Securities Regulatory Commission) have conducted more online and offline studies, aimed at helping investors to do more. . wise choices. (These studies have been on the rise since Xi’s assassination in 2019.) The government has also sought financial advisers and property managers to ensure that depositors complete a video test before deciding what to sell.

“We have done everything we can to meet the risks they expect to return,” said John Wang, owner of a Shanghai bond fund that has rejected many investors for their low-risk tolerance.

Most retailers find a guaranteed return (which is encouraged by the investment price) on established retailers, even though there are no real ones. Uncertainty can cause dissatisfied investors to complain to asset managers for providing false information.

However, the education campaign did not stop the spread of fraud. Court records show that last year the number of fraud cases worldwide increased by one-third from 2019.

The failure of this campaign is due to its small size. Many government-sponsored courses are accessible only to a limited number of students, for unknown reasons. Although many secret programs that run the financially secretive world are very popular, they face controversy over advertising for profit.

Worse yet, many educational programs are so comprehensive that they cannot explain what is required to prevent fraud.

“Teachers told us that big profits come with a lot of risks,” said Daniel Wu, a Zhejiang software engineer who studied economics before losing Rmb1m. “But he did not say which part of the corporate agreement we should read carefully to avoid getting caught.”

Although Beijing has established some of the world’s most comprehensive human rights laws, the process is relatively simple. Sun Yin, a professor at Southwestern University Politics and Law, told a newspaper last year that the lack of severe punishment for stealing personal information had left scammers “unsatisfied”.

Ji Shaofeng, Nanjing’s financial adviser and former banker, said a good education would help people to overcome fraud over time. “In the near future,” Ji said, “the rule of law is very important.”

However, as the news of corruption increases, many believe that education alone is not enough to combat climate change. Nie, an attorney who opposes fraud, said the lack of security of personal information allows fraudsters to create information so technically that victims feel it is impossible to deny it.

Jenny Fan, a fraudulent student who has been robbed, knows this from traumatic experiences. He says: “It is hard to phone a stranger when he knows so much about you. You just keep listening until you’re locked up.

Additional reports of Wang Xueqiao in Shanghai

Source link