India’s Covid disaster report: ‘No one has ever seen such a thing’

India is at the peak of the darkest period since independence was gained as the second most dangerous Covid-19 wave moved at full speed.

The country recorded more than 386,000 new cases on Thursday, as well as more than 3,500 people. Many experts say that the true figure is much higher.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his government is said to be exacerbating the problem by failing to prepare for it after allegations surfaced that the country was “at the end” of the epidemic.

The recent release has surpassed all that has endured since Covid-19’s first hit. It cuts across a wide range of economic, social and economic sectors, affecting the rich and the poor in rural and urban areas.

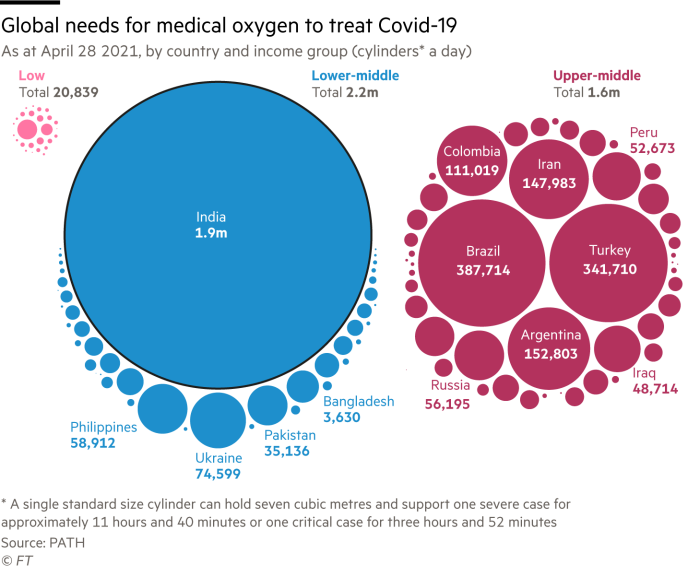

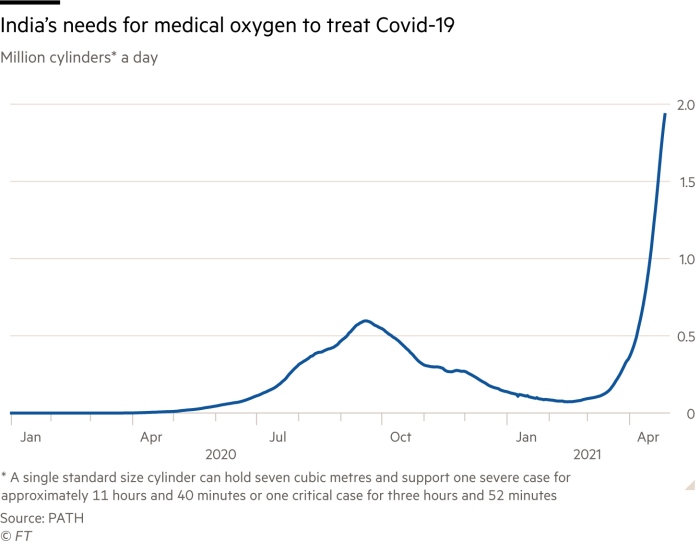

The crisis is exacerbated by a shortage of life-saving products such as gas and new Covid-19 models. The new closure also threatens to disrupt the resumption of the world’s fastest growing economy.

Here are four stories of four sufferers.

Aparna Hegde, a doctor in Mumbai

For the first time last year, the Aparna Hegde ward at the state-run Cama hospital for women and children had about 60 patients at a time. As the second wave in India grew, the number of patients rose to 100.

He said problems in hospitals revealed unpreparedness and medical neglect. India spends only 1% on sector growth.

“We don’t learn from our mistakes,” he said. “The first wave was over and we didn’t expect the second wave to come.”

The situation is so dire that Hegde was unable to find a hospital bed and the breath of a workmate in Delhi in an emergency. “This guy shouldn’t have died,” she said.

Hegde, co-founder of Armman, a non-profit organization that works with women and children, said the problem affects other areas of public health, which could have long-term consequences. Child protection services were disrupted and pregnant women were struggling to access care, she added.

“India should not be like this. That is a very painful thing, ”he said. “That’s why it hurts so much.”

Vishwanath Chaudhary, chief arsonist in Varanasi

The ancient city of Varanasi, on the banks of the sacred river Ganges, is where many Hindus want to be burned, who believe that they allow their lives to complete their journey to heaven and be freed from birth and death.

But the file for physical movement in Hindu cemeteries, as well as in Muslim or Christian cemeteries, it will never fail.

Vishwanath Chaudhary, 39, is raja, or the king, of the Dom caste, who has served all generations in the tropical heat of Varanasi.

With the number of bodies coming in daily rising to 100 – compared to as few as 15 last year – fires and jumps have become unbearable.

“Our family has been involved in managing the crematorium for generations. No one has ever seen anything like it, ”Chaudhary said.

“[Last year] it was not the same as what we see this time. Those things are dangerous, ”he added. “At times like this people get confused.”

The threat has led to a shortage of pyres wood, with retailers raising prices sharply.

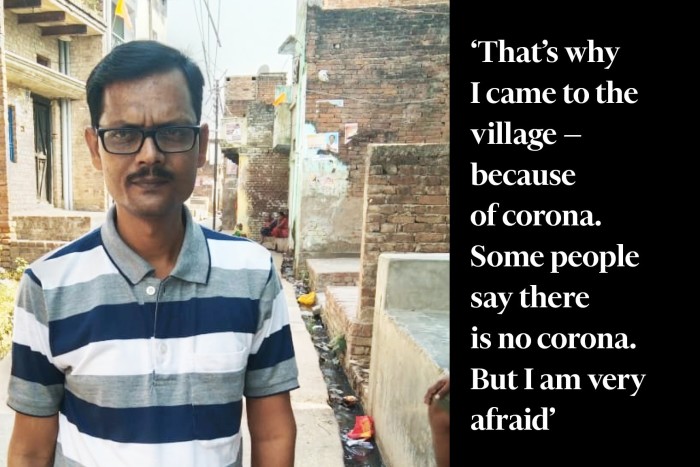

Ram Vilas Gupta, a migrant worker in Chandauli, Uttar Pradesh

More than 15 years ago, Ram Vilas Gupta left his family and village in the Indian subcontinent for the Mumbai metropolis, where he hailed a taxi and shared a room.

Like millions of other refugees, the 45-year-old was forced to return home in disgrace last year after the country entered the country and his money ran out.

When Indian cases dropped at the end of last year – and the economy is expected to recover – they returned to Mumbai and soon returned their monthly income to Rs18,000 ($ 243).

However, recovery is short-lived. By the end of March, after Mumbai encountered the second Covid-19 crash, its taxi customers stopped coming and their findings dried up.

Now back in their hometown and unemployed, Gupta has no idea how to repay the Rs40,000 he owed during a crisis last year. “What to do?” he said. “All my money [are gone]. It was very difficult. ”

The biggest fear now is that the virus, which is destroying the rural population in India, will have reached its village, where many still doubt its existence.

“That’s why I came to the village – because of the weather. Some people say that there is no air. But I’m very scared. ”

Sourindra Bhattacharjee, a university professor in Delhi

Like many others in recent weeks, 57-year-old Sourindra Bhattacharjee struggled to find her lover’s hospital bed.

Indians and high-income Indians enjoy access to medical care around the world, just as the poor rely on free public hospitals.

But now, even those who can afford it are trying to get help.

When the blood pressure of the older sister of diabetics in Bhattacharjee, Gouri, dropped below 80%, the business professor spoke to doctors who advised her to stay in the hospital. Proper blood pressure reading is over 90 percent.

But with enough beds in Delhi hospitals, all her attempts to help her sister have failed. In another emergency room he was rushed by a doctor who referred the boy to 13% respiration. “Look at his reading,” the doctor told him. “Tell me, who should we choose?”

“I realized there was no need to try,” Bhattacharjee said. “I brought him home.” He found his sister’s oxygen cylinder, but he did not have the necessary equipment to hold her.

Her sister is still with her at home as she tries to make sure she recovers – and to keep from getting the virus. “She looks fine,” Bhattacharjee said. “God has been good to me.”

Additional reports of Harry Dempsey in London

Source link