Hint: How Silicon Valley developed a system to convert blood into laboratory eggs

A few years ago, a young man from California who was a master of technology began to appear in one of the world’s leading biological laboratories. These labs dealt with the secrets of the embryos and were particularly interested in how eggs were made. Some think that by discovering this process, they will be able to copy and transfer each cell to an egg.

Their guest, Matt Krisiloff, said he wanted to help. Krisiloff did not know any biology, and he was only 26 years old. But after leading a research program at Y Combinator, a well-known San Francisco-based startup that was a first-time fund for companies such as Airbnb and Dropbox, he said, “well connected,” with the opportunity to invest in rich technology.

Krisiloff was also very interested in egg technology. He is gay, and he knew that technically, a man’s cell could be turned into an egg. If that were possible, two men would be able to have a child of their own. Krisiloff states: “I was intrigued by the thought, ‘When will homosexuality have children?’” Says Krisiloff. “I thought this was a reliable technology to do this.”

Today Krisiloff’s company started, called Contemplation, is the largest invention that follows in vitro gametogenesis, that is, the conversion of large cells into gametes — the sperm cells or the egg. It employs about 16 scientists and raised $ 20 million from well-known technical figures including Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI and former president of Y Combinator; Jaan Tallinn, one of the founders of Skype; and Blake Borgeson, co-founder of Recursion Pharmaceuticals.

The company is initially trying to make eggs on behalf of women. It’s scientifically easier than making eggs from male cells, and it has an obvious market. People are having children in life, but the healthy eggs that women get are in their 30s. This is the main reason why patients visit IVF hospitals.

Singing begins with blood cells from donors and attempts to convert them into the first “human egg” produced in the lab. The company hasn’t – yet no one else. There are scientific challenges to be overcome, but Krisiloff sent an email to his sponsors earlier this year that his launch could be “the first in the world to achieve that goal in the near future.” It says that artificial eggs “could be one of the most important inventions.”

NICOLáS ORTEGA

That is no exaggeration. If scientists could make egg products, they could break the reproductive system as we know it. Women without an egg — for example, because of cancer or surgery — can give birth to babies born to them. In addition, lab-produced embryos can remove female fertility limits, allowing mothers to have children between the ages of 50, 60, or older.

The expectation of egg cells from the blood is low — and rare. The process of making eggs from the original cells requires the muscles of the newborn. And if childbirth does not differ from what has been known in real life, there may be some unusual occurrences. It opens the door not only to the birth itself, but also to one or four individuals to produce offspring.

Indeed, because technology can turn eggs into a product, it can improve the process of reproduction. If the doctors were able to produce a thousand eggs for the patient, they would be able to reproduce them all and try to find the best eggs, counting their genes about future health or intelligence. Such a laboratory system may also allow for mutated genetic mutations in DNA-based technologies such as CRISPR. As Conception stated in a statement released earlier this year, the company hopes the artificial eggs could allow “genomic selection and mutation of embryos.”

Krisiloff states: “If you make the right choice to avoid Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, I think that’s a very important factor.” The commercial and health benefits can be enormous.

For scientific reasons, turning a human cell into a healthy egg is expected to be difficult, and Conception has not yet done so. But it’s part of the company’s business plans, too. Probably, when Krisiloff is ready to start a family, two men will be able to give the same amount of genetic IVF embryos. The biological mother was then able to carry the baby until it was time to leave. “I think it will end,” Krisiloff told MIT Technology Review. “It’s a question of when, not if.”

The tail of a mouse

This is how the technology of egg production can work. The first step is to take a cell from an adult — say, a white blood cell — and transform it into a powerful cell. This approach is based on the discovery of the Nobel Prize, a reprogramming prize, which allows scientists to move each cell to be “extraordinarily” — capable of producing any type of tissue. Next step: convert cells that are formed into eggs whose genetic makeup is similar to that of the patient.

It’s the last part that’s a scientific challenge. Some types of cells are easy to make in the lab: leave pluripotent cells in a bowl for a few days, and some just start beating like heart muscle. Some will be fat cells. But an egg can be a very difficult cell to make. It is a huge one — one of the largest cells in the body. And his biology is unique, too. A woman is born with enough eggs and does not produce any more.

In 2016, two Japanese scientists, Katsuhiko Hayashi and her mentor Mitinori Saitou, were the first to convert skin cells from mice to fertilized eggs, outside the body. They reports how, starting with the pruning cells, they incorporate these into stem cells, which gradually lead them to become eggs. Then, to complete the process, they implanted the eggs along with nerve fibers extracted from the intestines of a mouse. Instead, she had to make a small egg.

“Isn’t it a matter of ‘Oh, can I make an egg in a battery bowl?’ It’s a cell that depends on its position in the body, ”says David Albertini, a pediatrician at the Bedford Research Foundation.

An unexpected stranger

It was a year after rats discovered in Japan that Krisiloff began visiting biology laboratories to determine if the procedure could be repeated in humans. He was based in Edinburgh in the United Kingdom, connected with professors in Israel, and went to the headquarters of Hayashi at Kyushu University, in Fukuoka.

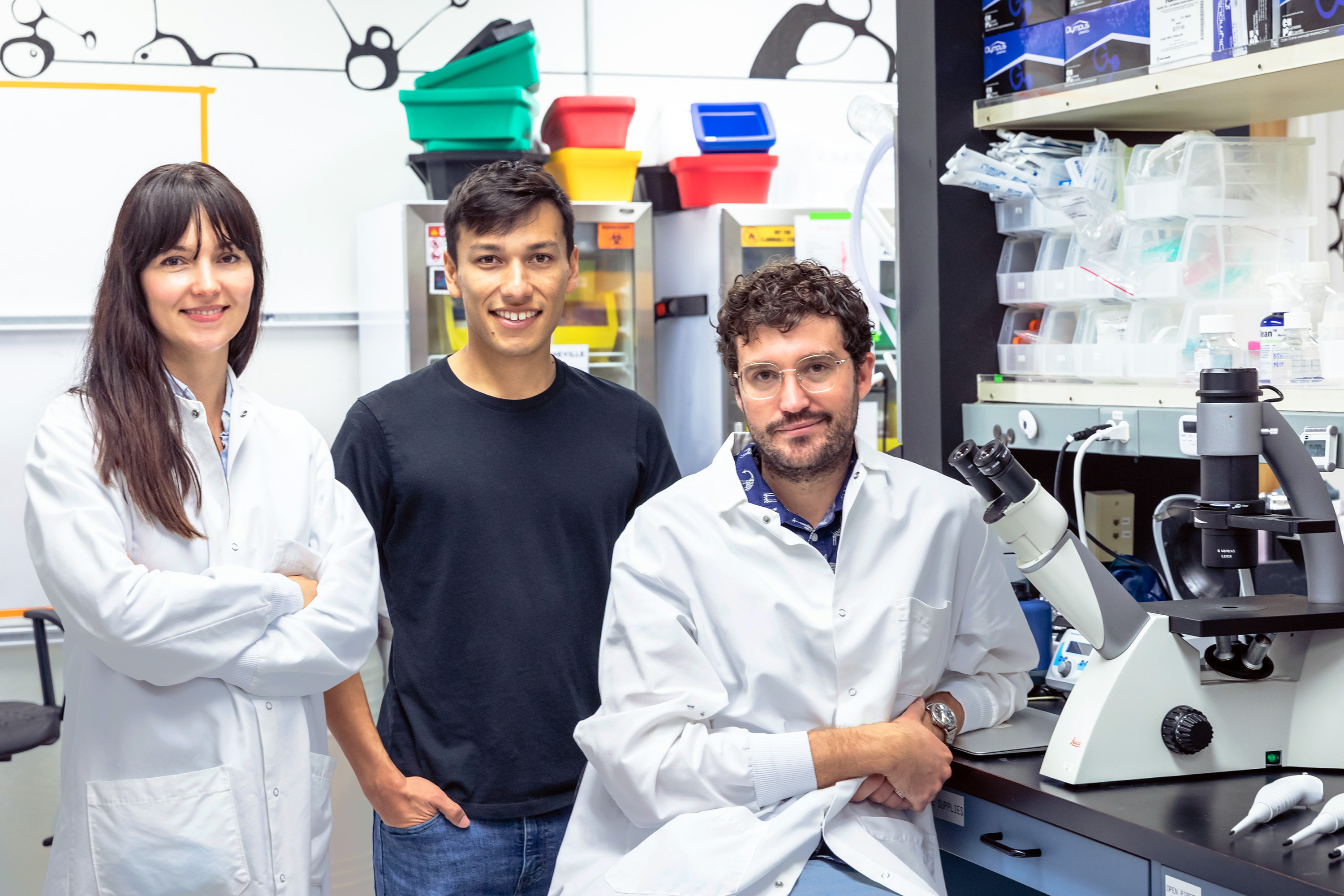

It was there that he met Pablo Hurtado González, a biologist who visited the academy, who linked Krisiloff as the founder of Conception. A third founder, Bianka Seres, an embryologist who works at the IVF hospital, later joined the group.

Krisiloff, a graduate of the University of Chicago, was the director of Y Combinator Research until then. Y Combinator is the most popular and well-established school in the world. His idea research work was providing money without sticky strings as a way to plan for the future in which jobs are taken up by machines.

CHRISTOPHER WILLIAMS

Krisiloff says he resigned after falling in love with Altman, the then president of Y Combinator. Although the relationship did not last long, the change in career freed him from the task of producing small eggs, with the first money from Altman. The company was originally called Ovid Research and changed its name to Conception this month.

Some researchers found that the young entrepreneurs were over their heads. The science of in vitro gametogenesis is overseen by a small group of university research teams who have been working on the project for many years. “When I spoke to them,” says Albertini, “they did not know anything, nor did they know how to start a business. They ask me what equipment I should buy. It was’ How would you know if you made an egg? What would it look like? ‘”

Another scientist who Krisiloff knew was Jeanne Loring, a molecular biologist at the Scripps Research Institute. Working with the San Diego Zoo, Loring had already assembled cells from one of the white rhinos in the north, species that are on the verge of extinction. He was amazed at the ability to produce eggs if he could resurrect them. Loring observes: “They are young and optimistic and have money in their pockets, so they do not rely on people to satisfy them. “Sometimes it’s just a matter of not being wise.”

What Krisiloff knew for sure was that reproductive technology could be equally of interest to savvy professionals such as AI or rocket space. As Stanford University obstetrician Barry Behr put it, “Today if you write ‘please’ on a cardboard box and take it to Sand Hill Road, you can earn some money.”

The problem with artificial gametes is that there will be no cure for many years — and there are serious side effects, such as who is to blame if every child is not healthy. Krisiloff did not see this as a barrier to organizing the company. In fact, he believes that many innovators should try to tackle the “hard” scientific challenges and that their findings could come as a fast-paced commercial investment. “My argument is that there would be a lot of money if people turned research organizations into for-profit organizations,” he said. “I’m a big believer in the important research that is going on in the company.”

Fetal muscles

Krisiloff’s company has never published a publication or captured the public’s attention. This is because his team did not produce a human egg, and he does not want to be seen as promoting the natural “vaporware”. Conception, Krisiloff says, is still trying to meet its first benchmark – which is to make a human egg and a legitimate way to make them.

This is also the goal of researchers like the Japanese who developed mouse eggs. But replicating success with human cells is difficult. Because the recipe involves imitating the natural steps in which the eggs are formed, the experiment lasts almost the entire time the pregnancy is in progress. That is not a problem for mice, which are born in 20 days, but in humans, any experiment can take months.

When I met Saitou and Hayashi, in 2017, they told me that copying mice technology into humans brought about another problem. Examining the exact procedure may require abortions: scientists have to extract follicle cells from human embryos or infants. The only way would be to learn to make the necessary cells from the stem cells as well. This, in itself, would require further investigation, they predicted.

At Conception, scientists began to experiment with the fetal nervous system, which they believe is the fastest way to obtain a fertilized egg. Krisiloff made strenuous efforts to obtain the articles — at another time tweeting for abortions directly. He also sought cooperation with UCLA and Stanford, although to no avail. He declined to say where Conception gets its donation money at the moment.

Examination of fetal tissue is acceptable but very difficult, and for some people it is very disgusting. During the Trump administration, health officials set new barriers, in addition to prompting abortion protesters to reconsider their support. Krisiloff says the company still uses human fetal tissue, but now it is often used to understand cells identified by major cell types so that scientists can try to re-create from original cells.