Carlo Rovelli and the physics of lockdown: ‘Not moving is paradise’

Carlo Rovelli takes a break from thinking about what might happen inside a black hole, his current preoccupation as a theoretical physicist, to appear on my computer screen from his Canadian home in London, Ontario. He immediately praises my soft background of a rather messy bookcase — in contrast to the hard brick wall behind him.

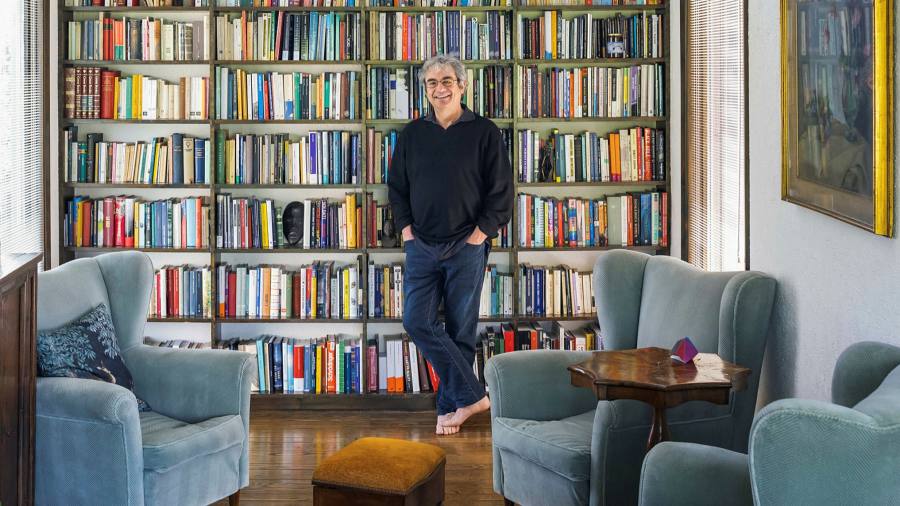

But Rovelli, who has emerged recently as the greatest contemporary populariser of physics, can shift scene almost as fast as a particle in a quantum experiment. He swiftly rotates his computer screen to display a huge and well-ordered bookcase across the opposite wall, before swivelling back to the bricks.

“When I’m in public I usually show the books,” he says, leaving me with the feeling that I am privileged to be facing the bricks — especially because my wall view also shows several items that tell a story about his Italian ancestry, which we go on to discuss.

Rovelli’s latest bestseller Helgoland, following on from The Order of Time and Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, is the clearest and liveliest of the many popular accounts of quantum physics that I have read. The book describes a “relational” universe in which there are no absolutes and everything depends on interactions between objects.

On the wall behind Rovelli is an oval-framed photo of his maternal grandparents as a young couple in Piedmont. It dates from the 1920s, a decade that plays a big role in Helgoland because of the intense intellectual ferment then as scientists laid the foundations of the new field of quantum mechanics.

“My grandmother Rosa Peretti was a remarkable woman,” says Rovelli, 65. “She was a teacher but mostly she did artistic things, particularly painting miniatures on ivory just an inch across. It was a dying art form even then. You need very good eyes and a very firm hand, because ivory takes colour in a very precise way.”

Nonna Rosa sold many of her miniatures but others passed down to her grandchildren, including Rovelli, who treasures them. He is well aware that in today’s climate many people would condemn the use of ivory but “she would not have conceived that she was doing anything wrong”.

The other oval frame on the wall contains what looks like a Renaissance portrait of a young man. “One day when I was a child, somebody came to our house and said: ‘That’s from the school of Raphael and might even be by him,’” Rovelli says. “So we called in an expert to evaluate it and for a while we talked about becoming billionaires — but it’s just a 19th-century copy or something like that.”

Also visible is one of a pair of vitrine display cabinets with curved glass doors. “They were a marriage gift to my mother just after the war. She had some friends in the Italian aristocracy,” Rovelli says. “I grew up in Verona with these two things in the living room and my mother kept telling me: ‘Be careful, don’t break them.’ After 60 years they’re intact but I still worry when I walk by. I hear the voice of my mother telling me to be careful.”

As we talk more about the interior of the house, it becomes clear that it is full of objects inherited from Rovelli’s Italian family. He shipped them out after moving to London in 2019, when his partner Francesca Vidotto accepted an academic appointment in physics and philosophy at the University of Western Ontario.

“We bought this large house soon after we arrived in Canada,” he says. “We fell in love with the place. It was built in the 1970s but there’s something oldish about it. We are close to the university and at the same time we have the forest nearby.” Rovelli briefly rotates his screen again so that I can see three large picture windows with a lawn and trees beyond.

The house has a bright and open, distinctly North American feel. The furniture juxtaposes softly upholstered modern chairs and sofas with harder Italian pieces from the 19th and early 20th century.

“After my parents died a few years ago, I didn’t know what to do with all their furniture and paintings. Nobody likes old furniture now so I put everything into storage,” he says. “Then I had it shipped here in a big container after we bought this house. I have a small apartment in Verona but I could never afford anything this size there.”

Rovelli was able to move with Vidotto to Canada because he had just given up his teaching duties at Aix-Marseille University in the south of France, where he has been a professor of theoretical physics since 2000 and retains his academic affiliation. He had expected to use the Ontario house as a base from which to travel between Europe and North America. But then came the pandemic “so I basically ended up here and I’ve not been moving for more than a year”.

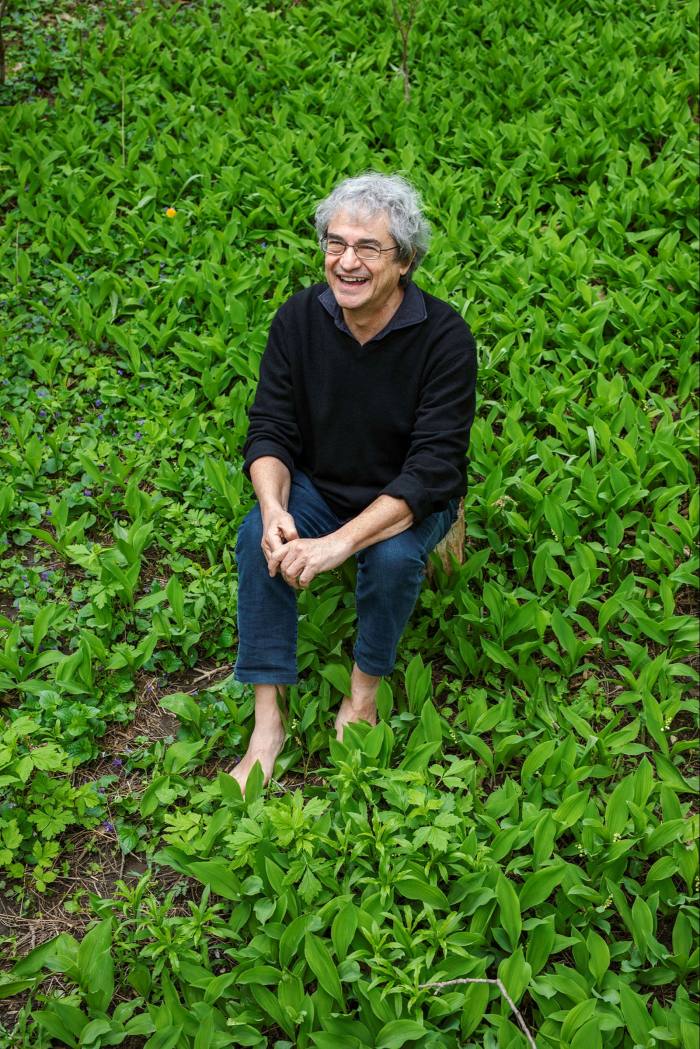

The lockdown has suited Rovelli well. “I am so happy,” he says with a smile showing that he really means it. “I love this openness to nature, these huge spaces, the fireplace, the wood outside, all these things. Being locked down in this place has been a pleasure. My life was travelling, travelling, travelling. So not moving is paradise.”

But he mentions one recent tragedy: the death of one of the married couple who translated his popular physics books, including Helgoland, into vivid English prose in a style much praised by reviewers. “Erica Segre passed away last month and she is a huge loss,” Rovelli says. “I want to express my immense gratitude to Erica and her husband Simon [Carnell].”

Segre, a native Italian speaker, was an academic at Cambridge university who specialised in Spanish and Latin American culture. Carnell is a poet. “They not only captured perfectly my meaning but they could completely render the feeling and sound of my Italian — and improve it, because their English language is remarkably beautiful and rich.”

Listening to Rovelli talking in almost perfect English with a gentle Italian accent, it is easy to imagine him writing in English too. “Yes, I write technical books and papers in English but when it came to writing for the wider public, I realised that I’m much better in Italian — and then having excellent translation. I’ve been reading a lot in English, but even today I’m more comfortable reading in Italian.”

During lockdown Rovelli has had time to engage with readers from across the world. “I receive many emails — a little too many. I read everything, sometimes just the first sentence and then I skip to the next one. But as soon as there is something interesting or if someone is particularly nice, I try to answer,” he says. “One reason is that it’s a good feeling to be kind to people. The other is that some of the questions posed are useful to me in rethinking my ideas.”

We turn next to an issue I had emailed to Rovelli: to what extent can our brains really grasp the underlying nature of quantum physics, relativity and the forces and particles that make up the universe. After all, we evolved to think about life in small groups on the plains and forests of Africa.

Rovelli replies first by emphasising the remarkable flexibility and learning ability of the human brain. “I can do mathematical calculations in a way that our ancestors certainly couldn’t,” he says. “Hundreds of years ago we had the difficulty of understanding that we live on a planet that goes around the sun and spins very fast but we digested that.

“Quantum mechanics or relativity is another step in the same process,” he continues. “I think a much harder mental step was for a species of hunters and gatherers to learn to grow plants that will produce crops six months later than it is for us today to learn about relativity.”

It is “the wrong perspective” to look at understanding the fundamental physics of the universe as a huge challenge that needs to be overcome with one great intellectual leap, he adds. “The right perspective is we have learnt something, then we learn something else, then we learn something more. We are capable of learning about our complex environment by taking incremental steps.”

Rovelli warns us therefore not to expect any great cosmological revelations soon — and not to get overexcited when new experimental results or observations are hailed as a huge leap forward. The latest example came earlier this year in experiments at Fermilab near Chicago; subatomic particles called muons seemed to behave in a way that hinted at the existence of a new “fifth force of nature” beyond the four — gravity, electromagnetism and two nuclear forces — that are already known.

“Of course, we all cheer for something genuinely new but nature has been very conservative in the last decades,” he says. “A lot of announcements of new and unexpected things have turned out to be false, so one has to be very careful. We shouldn’t jump up every time a newspaper says there’s a hint of something new.”

Science goes slowly but it does move ahead, Rovelli says. He anticipates progress in one of the biggest unsolved problems — his own field of reconciling gravity with quantum mechanics. The current “standard model” of physics is incomplete because it does not show how gravity, described by Einstein’s theories of relativity, works with quantum mechanics, which describes how particles behave on a subatomic scale.

“I expect that a combination of theory, experiments and more clarity will give us an agreed-upon quantum theory of gravity, which would allow us to understand better things like what happened at the Big Bang or what happens at the centre of black holes, which we don’t understand today,” he says.

House & Home Unlocked

FT subscribers can sign up for our weekly email newsletter containing guides to the global property market, distinctive architecture, interior design and gardens.

Sign up here with one click

He himself is “trying to figure out what happens in the centre of black holes”. Their nature makes it impossible to observe what goes on when the known laws of physics break down inside them, but they play such an important role in cosmology that physicists would love to know what happens to the matter sucked into them.

“Most great science has been done by people in their twenties and I’m in my sixties,” he says. “However I do have the hope and ambition that I can still contribute to real science.”

But Rovelli’s fans will have to wait a while for him to produce another popular science book. “I still look at myself as a scientist who writes books in his spare time,” he says.

“I finished Helgoland about a year ago, and I have not been thinking about writing another book since. Maybe in the future I will sit down and write one, but for the moment it is not in my mind. I need a strong motivation. My publisher is screaming at me to write another book — and I’m resisting.”

Favourite thing

In 1976 at the age of 20 Rovelli dropped out of university and went travelling on his own around the world. His pair of favourite objects remind him of the Canadian part of the trip, hitchhiking from coast to coast, when he fell in love with the country and vowed eventually to come back and live there. One is a photo of his orange backpack and the other is a cardboard hitchhiking sign saying “Please VANCOUVER”.

Clive Cookson is the FT’s science editor

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first