Rafa Nadal and me – a tennis love story

Maybe it was the name. Back in 2005, when I first came under the spell of Rafael Nadal, there were not many Rafaels (or Raphaels) to be found in Britain – we were a rare breed. Benítez had recently been installed as manager of Liverpool but I was no football fan. Instead I was fast on my way to becoming a tennis nut, yet my two previous favorite male players, the American Andre Agassi and the Russian Marat Safin, were fading or nursing injury.

Then along came this dark-eyed, scraggly-haired teenage Spaniard with explosive footwork, flamboyant strokes and a piratical dress sense. As he swung his way to his first major title at the age of 19, I put all my chips on him – this was my new guy.

Over the past 17 years he has richly rewarded me and his millions of fans for our loyalty, culminating in last Sunday’s wildly improbable triumph at the Australian Open, where he became the first man to win 21 grand slam titles. Of course he did it at the major tournament where he had the least success; of course it was just weeks after coming back from a six-month injury lay-off and a bout of Covid; of course it was against the dominant hard-court player of the past 12 months, Daniil Medvedev; and of course it was from two sets to love down over five and a half gruelling hours. Why? Because Nadal excels at doing things the hard way.

For proof of this, you need only look at any single stroke he’s ever played. The greatest left-hander of all time is in fact a right-hander. A segment filmed for Spanish TV in 2008 that can be found on YouTube shows him attempting to do simple tasks – write his name, throw a dart, brush his teeth – with his left hand. He is hopelessly cack-handed. Nadal can’t do anything with his left – except win 21 majors.

A young Nadal playing in the 2000 Les Petits As tournament © Corbis via Getty Images

It was his uncle Toni who made the switch, deciding it would give his nephew a tactical advantage, and who schooled the young Nadal on the red clay of the Manacor tennis club in Majorca. The 2011 autobiography Rafa, co-written with John Carlin, is full of stories detailing the elder Nadal’s uncompromising, borderline cruel approach: shouting, insults, making Rafa play without water if he forgot his bottle. “I knew he could take it,” said Toni’s frequent refrain. Another uncle provides further proof that something unyielding lies in family DNA: Miguel Ángel Nadal was a notoriously tough footballer who played for Barcelona and was nicknamed “La Bestia”.

It has become a truism to say that Rafa’s greatest asset is his fighting spirit and willingness to battle through adversity and pain. Days after that first French Open triumph that won me over, the young Majorcan flew to London to play Wimbledon. He had at this point played only a handful of professional matches on grass.

It was here that I first witnessed the man in the flesh. On an outside court, I found him playing his first and to this date only Wimbledon doubles match alongside the elegant serve-volleyer Feliciano López. I heard Nadal before I saw him. Today’s Nadal is a relatively slimline version but in those muscle-bound days he was, like his footballing uncle, a beast. I still remember the sound and the physical vibrations caused by his thundering around the sacred Wimbledon turf. (His own nickname, “The Bull”, was well earned and it made perfect sense to see him compete, years later, in Valencia’s Plaza de Toros in a Davis Cup tie.)

At Wimbledon in 2005: ‘I still remember the sound and the physical vibrations caused by his thundering around the sacred turf’ © Getty Images

Saluting the crowd after going out of the Australian Open in the fourth round in 2005 © AFP via Getty Images

A second French Open title followed in 2006 (his first grand slam final against Roger Federer) but still few gave this “dirt rat” any chance on grass. He had lost in the second round of Wimbledon in 2005 and no one believed his baseline-focused game, precision-tooled for clay, could be as effective on the lawns of SW19. Rafa, however, was undeterred and over the next few years doggedly worked on adapting his game to hard courts and grass (it helped that the Wimbledon courts had been slowed down since the serve-dominated decade of Sampras, Ivanisevic et al).

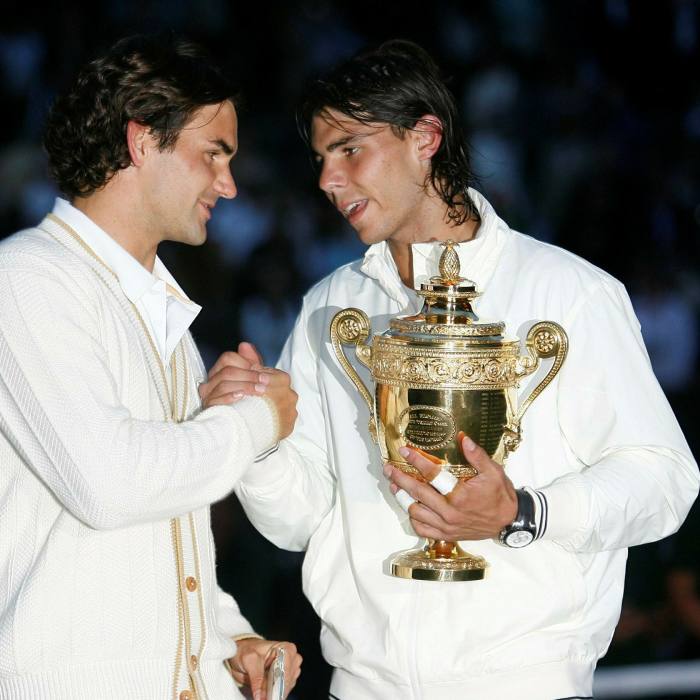

The 2008 Wimbledon final has become the most storied match in tennis history (see the excellent 2018 documentary Strokes of Genius), but what is often forgotten is that it was the climax of a trilogy: three titanic Wimbledon finals, the first two won by Federer in 2006 and 2007, the third by a disbelieving Nadal, who crawled over the line in encroaching darkness.

Roger Federer congratulates Nadal after their epic battle in the 2008 Wimbledon final © Popperfoto via Getty Images

Their rivalry has blossomed into a bromance, the two players revelling in their shared history © Getty Images

Everyone from David Foster Wallace to John Bercow has hymned the beauty of Federer’s game, and rightly so. While Nadal may not exhibit the balletic grace that the Swiss is famed for, I find his game beautiful the way a volcano erupting is beautiful: the gasp-inducing power, the bursts of speed, the unmatched topspin that in slow motion makes the ball flutter like a hummingbird’s wings. His “lasso” forehand motion, which finishes with him twisting his racket around his own head, is both spectacular and unique – club coaches warn against ever attempting it yourself.

The Federer-Nadal rivalry grew to become an exhilarating spectacle, and after the 2009 Australian Open final became a moving one when Nadal comforted a defeated and tearful Federer. Since then a bromance has blossomed, the two frequently seen giggling together off court and revelling in their shared history. In the early days there was often a real animus between the two fan camps; now there is an entente, perhaps one born in the face of constant threat from a common rival, the relentless Novak Djokovic. Even the most ardent Federer fans I know have softened, one telling me last week “I’m quite warming to this Majorcan” – and it works both ways.

Nadal demonstrates his unique ‘lasso’ forehand motion, which finishes with him twisting his racket around his head © AP

Not that Nadal is universally loved and nor is he perfect. The time he takes between points sent the Canadian player Denis Shapovalov into apoplexy during their quarter-final meeting last week. Even we diehard devotees will admit that Rafa is a faffer: over the years, the pre-serve routine of tugging, twitching and wiping has expanded to alarming and exasperating levels. Since the advent of streaming I’ve been taken to watching his matches on catch-up, the 15-second forward-skip button on my remote becoming worn down with overuse.

For Nadal this is all about control. Off the court, he assures us, he is positively easy-going, but when operating in his rectangular workspace everything must be just so. Anyone who has seen him meticulously repositioning his treasured twin water bottles on to just the right blade of grass knows this – and the memory of Lukas Rosol purposely knocking them over during a change of ends at Wimbledon 2014 still provokes a shudder.

What Nadal has been less able to control is the impact of his 1,038 match wins on his body. There have been injuries to the knees, abdominals, back, wrist, feet and more. After his six-hour defeat to Djokovic at the 2012 Australian Open, Nadal couldn’t stand; in 2014 he barely hobbled through the final against Stan Wawrinka. We stuck with each other through challenging times. I was there (OK, watching disconsolately from the sofa) as he pulled out of the tournaments and took three straight losses in slam finals to Djokovic. He was there for me (in the afternoon Australia) as I tried to get my baby son back to sleep at 3am in London, night after night.

Nadal has rued having been absent through injury from more majors than his Big Three rivals. Federer did not miss a single grand slam event between 2000 and 2015; and since his debut in 2005 Djokovic had missed only one until his deportation from Australia three weeks ago. Nadal has missed 11.

How many could he have won if he’d been consistently healthy? Nadal would detest the question. He doesn’t do hypotheticals. Asked by a journalist what the talented but mercurial Nick Kyrgios could achieve if he worked as hard as Nadal, the Spaniard snapped: “If. . . if. . . if. . . does not exist. ” Fellow pros and pundits agree: Nadal’s ability to focus on the matter at hand, to play each point as it was the last and not dwell on a missed shot, loss or injury, is unparalleled.

It has not been through choice but Nadal has learned to endure and to bounce back. “We need to suffer and we need to fight. That’s the only way to be where I am today, ”he said recently, reflecting on his career. But he also endeared himself to the Melbourne crowd with his sober acknowledgment of what they had been through during many months of painful Covid lockdowns.

Djokovic, the great gatecrasher, will no doubt in time eclipse Nadal’s 21 – perhaps even this year – and the GOAT debate will rumble on long after the Big Three have been put out to pasture and a new herd has taken over. For now, I’ll do as Nadal does and try to stay in the moment before the next bout of suffering begins.

Raphael Abraham is the FT’s deputy arts editor

Find out about our latest stories first – follow @ftweekend on Twitter